Local activists urge action from community in ongoing MMIWG2S+ crisis

Local activists believe the majority of Peace region residents would rather look the other way than face the hard truth of the ongoing MMIWG2S+ crisis.

Trigger Warning: This article contains discussions of violence, racism, and sensitive topics related to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA+ individuals (MMIWG2S+). Reader discretion is advised.

DAWSON CREEK, B.C. — Local activists believe the majority of Peace region residents would rather look the other way than face the hard truth of the ongoing Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ (MMIWG2S+) crisis that is still happening today.

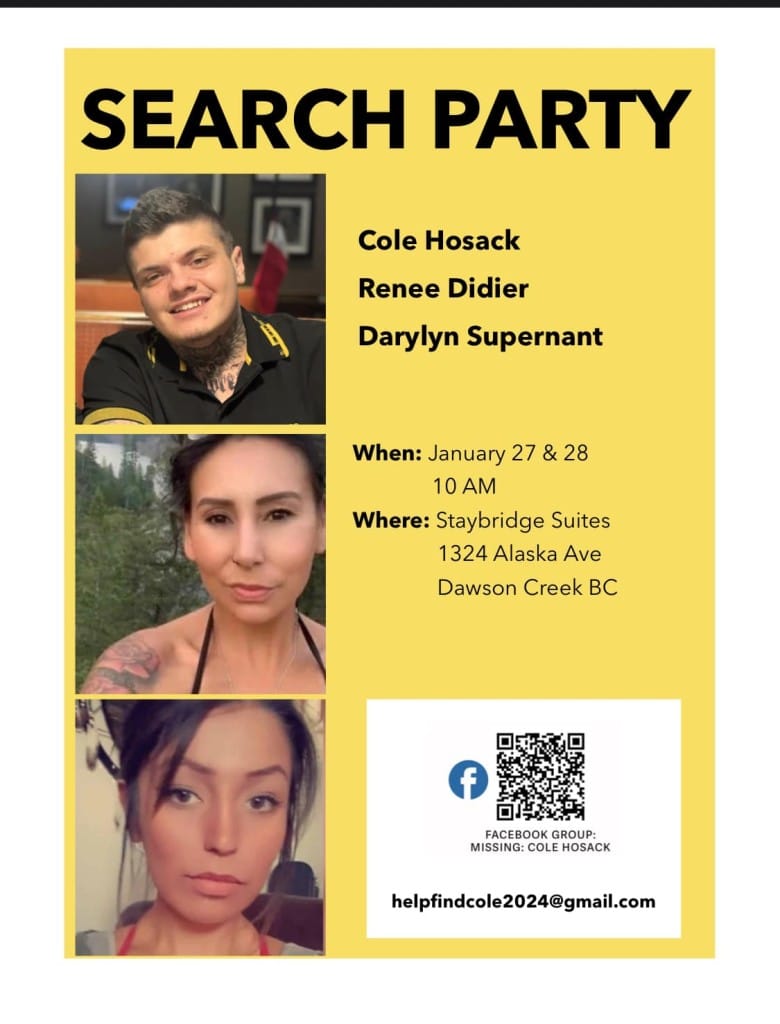

March 15th, 2024, marked the one-year anniversary of the disappearance of Darylyn Supernant, an Indigenous woman from Dawson Creek. At the time of her disappearance, Darylyn was 29 years old.

On December 7th, 2023, Darylyn’s cousin, 40-year-old Renee Didier, was reported missing by family and friends.

Both women were last seen in the Dawson Creek area. At the time of this article’s publication, Dawson Creek RCMP has not provided a progress update on the ongoing investigation of each woman’s whereabouts.

Public response to MMIWG2S+ hindered by apathy and racist commentary

Indian Residential School Survivors Society’s Northern Region MMIWG2S+ Coordinator Connie Greyeyes believes the response from the public would be much different if Renee and Darylyn were caucasian.

Latest Stories

“The community just doesn’t care enough, and it’s because they’re Indigenous,” said Greyeyes. “That’s the tough part about living in northeast B.C.”

Beyond ethnicity, Greyeyes listed a number of reasons why she thinks this is the case, beginning with a lack of consequences for those who vocalize racist comments surrounding MMIWG2S+ across multiple platforms.

“We have an MP, Bob Zimmer, who thinks it’s okay to say that [Indigenous women] wouldn’t go missing or be murdered if we just stayed on reserve, got jobs and were happy like they want us to be.”

Though Zimmer has since apologized, he appeared to receive no further consequences for his words.

Jan Atkinson, intensive case manager for the Nawican Friendship Centre in Dawson Creek, echoed Greyeyes’ sentiment.

“When we have people in power who make those comments — they are normalizing racism and hate instead of taking action against it,” said Atkinson.

The intensive case manager also believes that the general public doesn’t realize the capacity of the ever-present MMIWG2S+ crisis due to the absence of Canadian news on social media platforms.

“Because the news isn’t on Facebook, people don’t realize [the extent of the crisis], they think it’s a thing of the past, and it’s not a thing of the past,” said Atkinson.

“It’s kind of like people want to live with blinders on. There are those of us who know the reality [of the crisis] because we hear the stories. If [the general public] heard what we hear on a daily basis, they would know [the reality of the crisis].”

According to the Aboriginal Alert website, the organization reported 931 missing alerts of Indigenous people in Canada throughout 2022.

“Many were located, but too many were found deceased, and disturbingly, 141 individuals are still missing,” the website reads in its review of 2022.

Although Manitoba had the most missing alerts reported out of all provinces, Alberta and B.C. have the most missing alerts that are still active.

As of February 7th, 2023, there are still active missing alerts for 26 Indigenous people in British Columbia.

Mocking the pain and trauma of MMIWG2S+ on social media

Greyeyes, who describes herself as an “accidental activist,” described a more recent occurrence where two women posted a photo on Facebook of themselves in what appeared to be the washroom at LoneStar NightLife in Dawson Creek, with the caption “Hey we didn’t go missing!!.”

The nightclub was one of the last places Renee, who is Greyeyes’ cousin, was seen before her disappearance.

“When you consider this huge trauma that Indigenous people of Canada have endured — it’s an extra slap in the face when people like [the girls in the Facebook post] think it’s funny to mock something like that, to mock somebody’s pain,” said Greyeyes.

“It’s real pain, it’s f***** up. I don’t care who you are — I don’t know any good person who would think it’s okay to do something like that.”

The woman who posted the photo apologized shortly after. Still, Greyeyes questioned the woman’s authenticity and said she was shocked to see the number of non-Indigenous people defending and supporting the woman in the comments under her apology.

“None of my family would have ever posted something like that because we’re raised right,” Greyeyes said, disbelievingly.

“We were raised to care about other people, to have empathy and be considerate. The amount of people who jumped to defend that [post] is alarming, and that is why it’s ‘okay’ when we go missing.”

Greyeyes also attributes the lack of awareness surrounding the ongoing MMIWG2S+ crisis in the region to stigmas and misconceptions based on assumptions about Indigenous women’s lifestyles.

“When my cousin Renee went missing when Darylyn went missing — there were no alarm bells because, you know what? Us Indian girls and us Indigenous women and girls, we like to go and party. We don’t care about our kids,” said Greyeyes. “That [stereotype] is attached to us.”

According to Greyeyes, what may appear as an Indigenous person using substances or suffering from addiction issues is, in reality, a person trying to cope with years and years of intergenerational trauma.

“When you see people that are in the streets who are alcoholics or drug addicts — I don’t see them that way. I see people who are deep in trauma, who are suffering, and for a reason,” said Greyeyes.

“Their parents went to residential school or day school, they attended residential or day school. They don’t have the time, resources, or even the mental capacity to deal with their trauma. They’re just trying to survive.”

An article titled “Indigenous Perspectives of Trauma and Substance Use” on the B.C. government website provides background to Greyeyes’ statement.

“The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up to raise awareness of the impact of the residential school system in Canada, states, “Many students who spoke to the Commission said they developed addictions as a means of coping” with the traumatic events they experienced,” the article reads.

Greyeyes breaks her silence on Renee Didier

Greyeyes reluctantly shared her thoughts on her cousin’s disappearance, something she has chosen to stay silent about until now.

“Renee is a cousin I deeply, deeply care for and care about the path she was taking,” said Greyeyes. “When we don’t deal with trauma, we find other ways to numb it.”

According to Greyeyes, another misconception that surrounds Indigenous women is that they don’t love their children “enough to want to quit, or enough to make the change that’s needed.”

“I may not know exactly what you’re going through with your missing loved one, but I can see what I’m going through with how I’m missing Renee,” said Greyeyes.

“I know that she would never take off on her children or not be in touch with them. I know that she wouldn’t do that to her family. That’s why I kind of have been silent about it. The thoughts of possibilities are too painful. They’re too painful to think about.”

The possibilities of what may have happened to Renee, Darylyn, and so many missing Indigenous women are endless and remain unanswered to this day.

Catch-and-release approach to criminals creates fear in the community

Atkinson believes their disappearance is connected to the evolving morale of gangs involved in the drug trade in Dawson Creek.

“Unfortunately, it’s one of those things that is like a necessary evil — we’re always going to have some form of organized crime,” said Atkinson. “That is something that will never go away.”

According to Atkinson, in the past, there was an unwritten rule in place among criminal organizations that women and children should remain untouched and unharmed, regardless of the state of conflict.

“There’s a new wave of gangs now, and anything is on the table,” said Atkinson.

“[The gangs] are just ruthless and merciless.”

Though Atkinson believes the Dawson Creek RCMP are doing everything they can to keep organized crime in the city under control, she says the problem is the provincial justice system’s catch-and-release approach to criminals.

“We did just recently have somebody who was arrested for a fairly major offence, and the judge let him back into the community the next week,” said Atkinson.

“It’s so disheartening when somebody is arrested who has created fear in the community, and then to have them released just within a couple of days — it’s scary.”

The fear created within the community may prevent residents with information on the whereabouts of missing people from going to police.

Those with information who feel uncomfortable going to RCMP alone can contact the Nawican Friendship Centre at 250-782-5202 for an advocate.

Last Sunday, the Dawson Creek RCMP said in a release it had arrested and brought 11 new criminal charges against 29-year-old repeat offender Tanner Murray.

In the release, RCMP express doubts about being able to keep Murray in custody despite his long list of charges.

“Police have applied to keep Tanner in custody, however, it is expected he will be released back into the community,” said the release.

Dawson Creek Mayor Darcy Dober says the city has “been working quite closely with the RCMP to make sure they have the staffing and resources they need to work effectively in the community.”

“In February, myself and the [City of Dawson Creek] Chief Administrative Officer travelled to Victoria to meet with the Attorney General (of B.C.) Niki Sharma and the Minister for Public Safety (of B.C.) Mike Farnworth to lobby for support for our RCMP and for improvements to our local justice system,” said Dober.

The mayor says he and city staff also have weekly meetings with Dawson Creek RCMP Staff Sergeant Rob Hughes to ensure they’re kept up to date with what’s happening in the city “from a law enforcement perspective.”

“The city has also added an additional bylaw enforcement officer to assist on some of the issues that we’re seeing in our downtown areas,” said Dober.

The mayor extended his sympathies to the families of Darylyn and Renee, as well as Cole Hosack, a 24-year-old who was reported missing by friends and family on January 1st. Just like Renee, Hosack’s last known location was LoneStar NightLife in Dawson Creek.

“It’s never easy as a mayor to hear about situations like this. There have been concerns voiced in the community over the past year since Darylyn, Renee, and Cole went missing,” said Dober.

“The role I have as a mayor is to continue reassuring our community that we are in constant contact with our local RCMP detachment. We’re always looking at ways that we can advocate for our city in regard to resources. We are grateful for the extra members and units that came to assist our local members.”

Mayor Dober says he keeps Darylyn, Renee, Cole and their friends and families in his thoughts daily, and assures the local RCMP are “still working hard towards finding answers.”

Federal government issued “failing grade” for continued inaction on MMIWG2S+ crisis

Outside of support from RCMP and local government, a local organization in Dawson Creek has taken extra steps to provide a safe space for Indigenous women in the community by accessing funds made available by the province.

The Nawican Friendship Centre in Dawson Creek was one of 20 organizations in B.C. to receive funding from the provincial government’s Path Forward Community Fund.

Announced in 2022 by B.C.’s Public Safety Minister, the provincial government committed $5.34 million to the fund, which is managed and distributed by the B.C. Association of Aboriginal Friendship Centres (BCAAFC). The fund’s purpose is to help end violence against Indigenous people, specifically women and girls.

According to a release from the BCAAFC, the Nawican Friendship Centre used the funding for its Next Steps project.

“The Next Steps project will create two rooms for Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people that are at risk of homelessness,” said the release.

“By creating medium-barrier, culturally-safe temporary shelter, the project will ensure the immediate success of those fleeing domestic violence and other unsafe situations.”

While support from local and provincial governments, along with the RCMP, appears to be present, the federal government continues to fail to meet the commitments it made to MMIWG2S+ and their loved ones.

In 2019, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls released its landmark final report, which included 231 Calls for Justice directed at federal, provincial, and Indigenous governments, institutions, social service providers and all Canadians.

Two years after the final report was released, the federal government released a National Action Plan (NAP) to address the calls for justice.

In January, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) released a resolution titled “Call for Canada to Implement the National Inquiry’s 231 Calls for Justice relating to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirit (MMIWG2S+).”

The resolution, which was presented during a Special Chief’s Assembly on December 5th, 6th, and 7th of last year, states that “since the implementation of the National Inquiry’s Final Report, minimal progress has been made to support and implement the Calls for Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ peoples.”

According to an article published by the Canadian Press last October, a Statistics Canada report found that homicides of Indigenous women and girls are less likely to result in the most serious murder charges than cases in which victims were non-Indigenous.

The study looked at how homicides of Indigenous women and girls moved through the court system and how the outcomes of those cases compared to those of non-Indigenous women and girls.

More than half of cases involving non-Indigenous women and girls between 2009 and 2021 resulted in charges of first-degree murder.

But when the victim was Indigenous, police laid or recommended that charge half as often. The less serious offences of second-degree murder and manslaughter were more common.

During that time period, Indigenous women and girls were killed at a rate six times higher than that of women and girls who were not Indigenous.

The StatCan study said 87 per cent of homicides of Indigenous women and girls between 2009 and 2021 were solved, compared to 90 per cent of cases where the victim was a non-Indigenous woman or girl.

Both categories had the same conviction rate of 55 per cent.

The report also said most Indigenous women and girls were found to be killed by someone they knew, and those accused in most cases were also Indigenous.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) has been tracking the progress of the federal government’s implementation of its NAP.

An NWAC release dated June 1st, 2023, issued the government a failing grade for “continued inaction” on its plan.

“If it was a school report card, the federal government would be given an ‘F’ for fail,” states the release.

How the community can get involved and show support for MMIWG2S+

When the federal government falls short of its commitments, Peace region residents are known to use their voices to advocate for their beliefs.

Examples of this include the residents who attended the “Axe the Tax” rally that occurred in early April, which protested the federal government’s implementation of the carbon tax, and the community members who continue to gather for the Freedom Convoy each Saturday along the Alaska Highway.

Yet, according to Greyeyes, the number of residents who show up and show support for MMIWG2S+ is minimal.

“We’ve had vigils here — they were never really attended. That’s the reality of it,” said Greyeyes, a Cree woman from Bigstone Cree Nation in Alberta who was born and raised in Fort St. John.

“It’s not too much to take an hour or two out of your time to come down and say, ‘Hey, you know what? I see you, and I’m sorry that you’re going through this, and I’m going to do my best to try and support you even if it means coming for a walk with you, which doesn’t cost anything.’”

Peace region residents will have the opportunity to show their support on May 5th, which is the National Day of Awareness for MMIWG2S+, also known as Red Dress Day.

“I think that the general public thinks it may not be their place to show their support, or maybe they don’t know what to say or don’t know ways that they can help,” said Greyeyes.

While Mayor Dober says the City of Dawson Creek is “looking at ways it can support and participate in Red Dress Day,” it is unclear how the City of Fort St. John plans to show its support this year. Energeticcity.ca reached out to city staff but did not receive a response by the time this article was published.

Last year, the city hung a red dress in council chambers and posted it on its social media in recognition of Red Dress Day. During the evening, the Centennial Park Stage lights were also illuminated in red.

The Fort St. John Metis Society is inviting community members to honour MMIWG2S+ at its Red Dress Day event on May 5th, which will be held at the Festival Plaza from 12 p.m. to 3 p.m.

Atkinson wants non-Indigenous residents to know they are welcome and encouraged to attend events held by Indigenous organizations.

“I understand that for some people, it’s awkward to walk into, but when the [MMIWG2S+] march happens on May 5th, show up. You are welcome,” said Atkinson, encouraging attendees to wear red.

“The reason we wear red is because that’s the colour spirits can see.”

Greyeyes also encourages non-Indigenous residents, “from the outside looking in,” to get involved in showing support for MMIWG2S+ in the community.

“It’s time for people to step out of their comfort zone and take that opportunity to learn.”

Beyond Red Dress Day, Greyeyes says there are many ways community members can show support and keep the awareness alive for MMIWG2S+, such as sharing social media posts on missing individuals or donating money for food or fuel to search parties.

“Maybe go out and help search [for missing individuals], maybe bring some sandwiches [to search parties], just do something to show somebody, ‘You know what? I see you, and I care, and I am sorry you’re going through this. Here’s what I can offer,’” said Greyeyes.

“I know Cole’s mother would probably appreciate that. I know Renee’s and Darylyn’s families would appreciate that. Let’s give those families a little bit of peace of mind and bring them home where they belong.”

Anyone with information on Darylyn Supernant, Renee Didier, or Cole Hosack’s whereabouts is encouraged to contact the Dawson Creek RCMP detachment at 250-784-3700.

Greyeyes says community members can also show support by being vigilant in “calling people out on their racism” on social media.

“Your silence speaks volumes when you witness racism and disrespect to the pain and trauma [of the families of missing individuals], and you don’t say anything,” said Greyeyes.

Peace region residents who would like to show support for MMIWG2S+ in other ways can donate to the Native Women’s Association of Canada, a non-profit, national Indigenous organization.

Residents can also take action against Indigenous women and girls by joining Amnesty International’s No More Stolen Sisters campaign. More information about the campaign and how to join can be found here.

Another way to contribute towards changing the narrative surrounding MMIWG2S+ is by getting educated and staying informed.

The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls says a permanent commitment to ending the genocide against MMIWG2S+ requires addressing the four pathways explored within the report.

These pathways include historical, multigenerational, and intergenerational trauma, social and economic marginalization, maintaining the status quo and institutional lack of will, and ignoring the agency and expertise of Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.

Read the report here.

Indian Residential School Survivors, Intergenerational Survivors and their families can receive emotional support and crisis counselling through the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

More information on services provided can be found here.

Community members interested in donating to the society can learn how to provide support here.

With files from The Canadian Press.

Stay connected with local news

Make us your

home page